An ice adventure!

Looking across the glacier at the mountains beyond

Vatnajökull is Iceland’s largest glacier - in fact, it’s the largest glacier in Europe by volume, covering an area of around 7900 km2. It covers around 8% of Iceland and contains some of the most active volcanos of the country including Bárðabunga, Öræfajökull, and Grímsvötn. It was used as a film location two Bond films; A View to a Kill, and Die Another Day, as well as Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, Interstellar, Batman Begins, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty and Game of Thrones.

It was also the destination for our latest adventure. Last year, before I came out to Iceland, Matthew and the rest of the team at work visited Vatnajökull to see the blue ice caves. It was something I very much wanted to do, but we’d had to wait until winter as each summer the ice caves melt and then re-form elsewhere when the winter comes. We decided to make a complete day of it and incorporate a hike on the glacier itself as well. After having had to postpone the trip due to catching Covid a few days before we were due to go, we finally made our journey along the south coast to the glacier. We chose to use the same excellent company as they used last year, Glacier Adventure, based in Hali - just a few kilometers beyond Glacier Lagoon.

Our day began early as we gathered at Glacier Adventure’s base camp in Hali where we met our guide Žanet, and were briefed about the day’s activities. As we had woken up to torrential rain, we were worried the hike may not be on, but when we asked, Žanet looked vaguely confused and with a shrug said “Of course. It’s just a bit of rain!” We also got kitted out in deeply unattractive but essential blue waterproofs, hiking boots, helmets and harnesses and were fitted for crampons, for the glacier hike. I don’t think I’ve ever worn quite so many layers before!

Žanet and the Glacier Adventure super jeep

There were only 6 of us in the group - for this kind of hike, 8 is the maximum they will take - and so there was plenty of room in the Glacier Adventure 4x4 super jeep for us all. Žanet had promised us a fun drive and so it proved, as we headed out towards our destination of Breiðamerkurjökull which is one of the outlet glaciers (that look like fingers) at the outer edge of Vatnajökull. After a short spell on the road, we headed off-road towards the glacier, bouncing and lurching wildly as the jeep followed an old farming road called “Þröng”, criss-crossed with ditches, pools and slopes and made its laborious way across the glacial outwash plain. More like a rollercoaster than a road, it’s not a route I would want to ever drive, but Žanet clearly had a whale of a time as she expertly navigated the pitted and rocky route, all the while regaling us with facts about the glacier and even running a fast-paced quiz, awarding points for correct answers about all things glacial and periodically testing us as to whether we had remembered and could pronounce the name Breiðamerkurjökull!

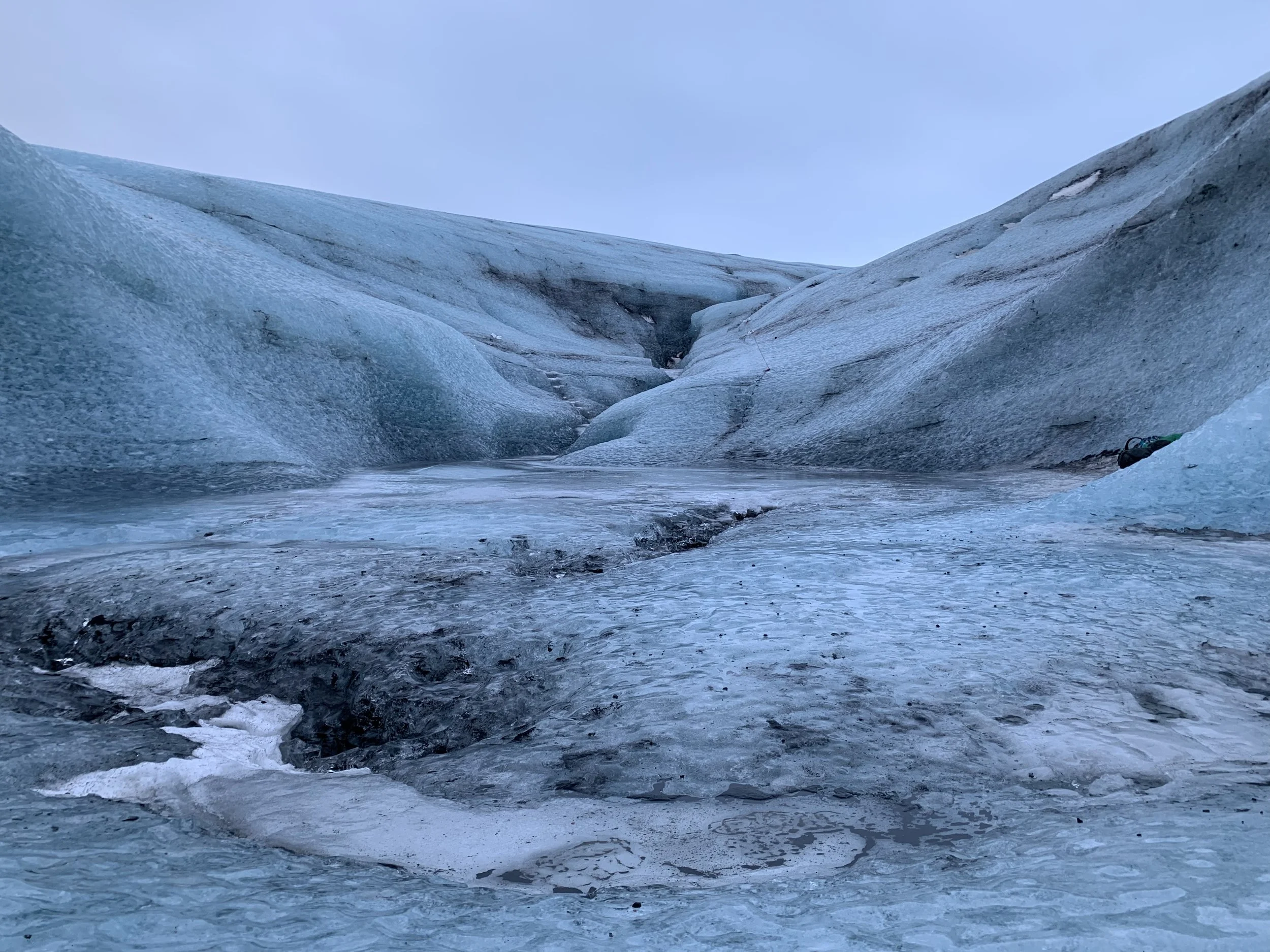

When we finally arrived at the place where the jeep could go no further, we still had a 20 minute or so walk to the edge of the glacier itself, so we set off, making our way across a rocky landscape with many icewater streams running through it from the glacier. When we got to the edge of the icecap we could see the majestic ice-covered volcano, Öræfajökull as well as Breiðamerkurjökull itself stretching ahead of us. The next thing we saw was the entrance to the blue ice cave to our left. Having noted that there were several groups already exploring the cave, Žanet suggested we do the hike first in the hopes that it was quieter on the way back so we painstakingly got our crampons on and set off over the ice.

What an amazing experience this was. Learning to ‘stomp’ down on the ice so that the teeth of the crampons could get purchase on the deep and slippery ice without skidding and slipping, we followed the ropes marking the route over the ice. Miraculously, the rain that had been so heavy all morning had almost stopped, so we had great conditions for our hike. Keeping together as a team, we used the ropes and carabiners attached to our harnesses to keep us linked to the rope at all times. We had been warned on no account to ever unclip a carabiner without the other one being firmly clipped to the rope, so that if we were to slip there would always be one point at which we were still attached. As we made our slow progress across the ice, we would come to points where the rope was anchored to the ice, or knotted to the next section, which necessitated unclipping one carabiner and reattaching it on the other side of the knot before unclipping the second, and then holding the rope up to make it easier for the next hiker in the line. Working as a team, we traversed the undulating surface of the ice together, stopping to gawp at the sheer size and scale of the glacier. Žanet pointed out the shafts and sinkholes, called moulins (from the French for ‘mill’) formed when summer meltwater streams on the surface of the glacier find a crevasse or other weak spot in the ice and begin to pour down through the ice. As the water moves downward, its turbulence and heat creates a narrow, tubular and vertical shaft, up to 10 metres wide, that can go all the way down to the bottom of the glacier, hundreds of metres deep.

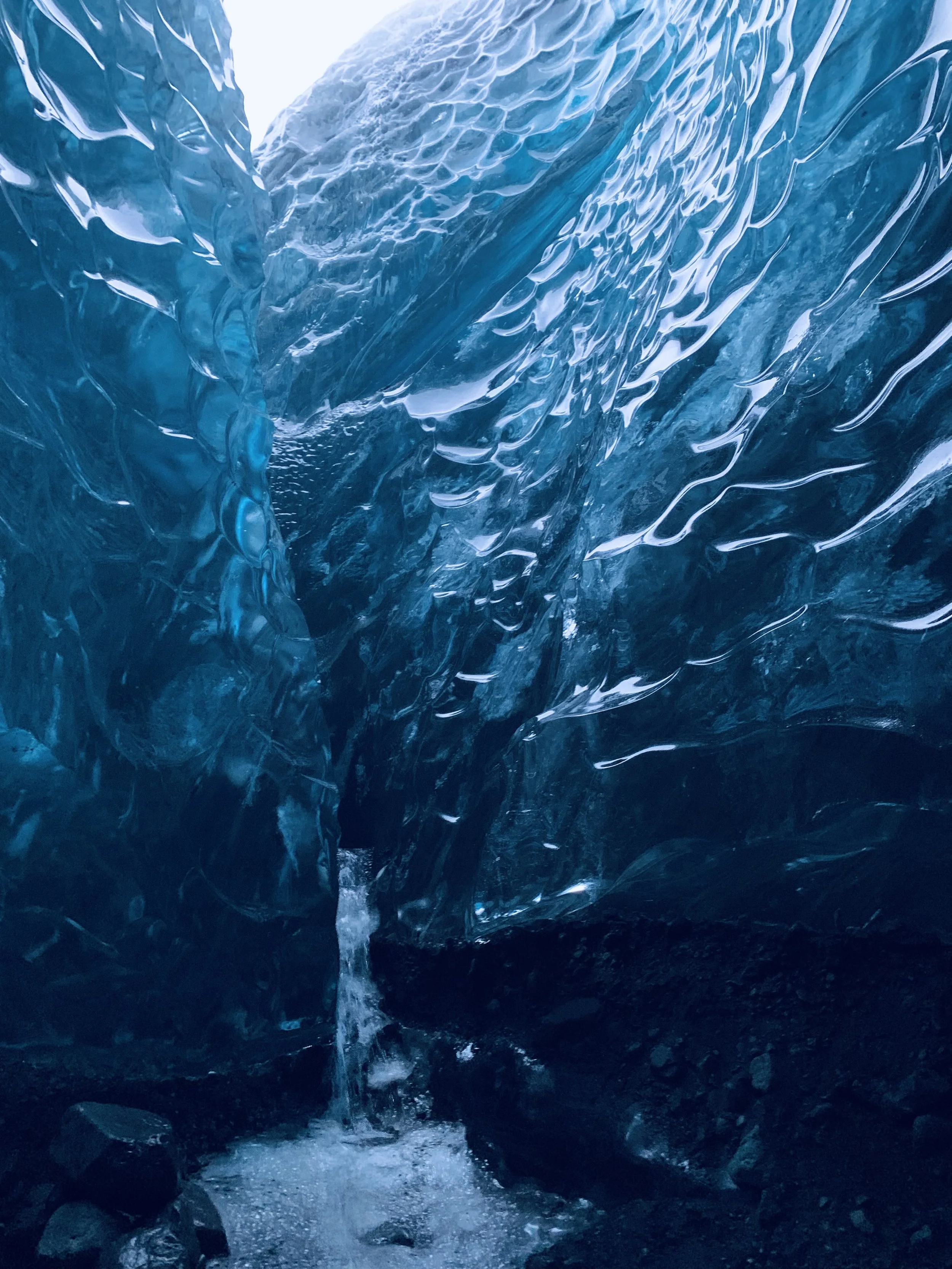

What I hadn’t been prepared for was the opportunity to actually climb down part of one of the moulins, clambering back up an almost vertical shaft of solid smooth ice. One by one, we unclipped ourselves from the safety of the ropes and went to explore the narrow route down into the ice. As we made our way down the narrow crevasse, the fast-flowing stream of water running down the bottom of it meant that we had to make our way down astride the bottom of the V with crampons digging in on the almost vertical sides of the V. Getting up the sinkhole necessitated a combination of digging in the tips of our crampons and pushing upwards, at times scrabbling and slithering upwards, to the next tiny ledge. Given how slippery it was, and how cramped and confined the vertical tunnel, it was so far outside my comfort zone as to challenge me physically and mentally, possibly more than anything else I have ever done in my life. It was only the fact that I knew there were 5 people behind me that kept me going at times. I have to admit, this is one of the most frightening things I have ever done. I am just glad that I hadn’t known beforehand that we were going to do that, as I would have been a nervous wreck by the time we got there. I’m not sure whether I was more scared of becoming stuck in this narrow ice chute - triggering claustrophobia that I didn’t know I had - or slipping and hurtling back down the ice chute to the bottom of the crevasse!! However, outweighing both those fears was the fear of being the one member of the group who couldn’t do it and having to go ignominiously back the way I came, so somehow with help and encouragement from Matthew and a hand-up at the end from one of my fellow team-members I got to the top. I probably won’t ever do it again, but by golly I’m proud that I did it!!!

The descent into the moulin. Narrow passageways of sheer ice with water flowing down the floor of the crevasse, passing a mini waterfall, looking up at the route out and being helped up from the top.

We then headed back to the ropes, re-attached ourselves, and set off back the way we’d come. By this time, we were much speedier, having become a little more practiced or, in my case, on such a high from having negotiated the moulin that I felt I could do anything!

Looking up from the the top of the moulin before we headed back the way we’d come

When we reached the edge of the ice again we were able to take the crampons off and enter the, by now almost empty, cave. As we stepped into this strange new magical blue world, it was like nothing I’ve ever experienced. Standing at the gigantic entrance to the Ice Cave, the texture of the ice glistens in the sun. Looking ahead, you can see endless shades of blue descend all the way to a point where all becomes darkness. The blue ice arch is spectacular, and as you look up, the ceiling above you is a mass of scalloped blue waves of ice - just stunning. The floor of the cave at its lowest point was a turbulent river of ice water rushing and tumbling down the slope, but in fact the very day before there had been no river at all, just a flat floor in the cave. The 24 hours of torrential rain that we had had leading up to our trip had changed the place completely.

The river of glacier water rushing down the floor of the ice cave

I know we had been told we were going to a blue ice cave, but I had never imagined it would be so very blue! Apparently, glacier ice looks blue due to the density of the ice. It is much, much thicker and denser than regular ice, e.g. the ice cubes in your freezer. It’s a result of a process that takes hundreds of years of snowflakes falling and compressing and re-crystallizing into ice, during which air bubbles trapped in the ice will be pushed out. When a chunk of ice becomes too dense to have any air in it, the light can travel deeper. The deeper the light travels, the more of the red-coloured spectrum gets lost along the way, making the ice appear blue to our eyes. Which is why the glacier ice in Iceland has that magical, otherworldly shade of blue. It is absolutely incredible, and we stood for what seemed like ages, just mesmerised by the place.

Matthew and I standing at the entrance to the ice cave

Žanet explaining to Matthew how the ice cave had formed

It was incredible to look upwards at the roof of the cave and realise that there were literally tons of ice above our heads and that we were standing underneath the area we had just trekked across.

One of the inlets formed by water, with a mini waterfall still flowing down into the river

Who knew what an amazing place lay under the glacier itself!!!

After another 20 minute hike across the rocks of the outwash plain, we came back to our jeep and did the whole whole roller-coaster trip all over again, back to the main road and base camp to peel off the many layers of clothing and make a very welcome hot chocolate - the best possible finish to an outstanding experience. Without doubt, this was the most amazing experience we have yet had in Iceland. The vast scale and age and magnificence of the glacier is humbling, and I for one feel incredibly privileged to have experienced a day out on - and under - Iceland’s biggest glacier.